The Levante players packed their bags to face a month of travel and kilometres in November. The blue and reds travelled the length and breadth of the Iberian Peninsula to face the story of the league competition in the Grupo Segundo universe of the Silver category. It was a kind of full-blown pilgrimage as 1957 drew nearer to its official farewell. The roadmap was set. Eldense, Alcoyano, Cádiz and Huelva made up the most travelled version of Levante. It was not a fact to be attributed to the randomness of the calendar. Nor was it a chance occurrence of a strictly sporting nature. In the first days of November 1957, the devastating effects of the October floods, which devastated the city of Valencia, marked the destiny of Levante’s society during November.

The terrible storm ravaged the Vallejo fiefdom. Its consequences were annihilating. The blaugrana team’s stadium was completely flooded by the virulence of the rain. The river Turia overflowed its banks as it passed through the capital, causing absolute chaos and Dantesque images. Vallejo suffered the onslaught of the rising water. It was barely a few metres from the Turia riverbed. The losses were considerable. The reports issued by club officials put the cost of rebuilding the coliseum at around one million pesetas. The amount was as remarkable as it was burdensome for the economic records of the time.

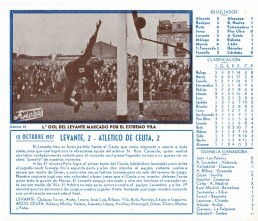

The apocalypse seemed to be looming over Valencia on Monday 14 October. That Sunday 13th (matchday five) Levante had faced Atlético Ceuta in Vallejo (2-2). Perhaps at that moment in time, no one could have imagined the magnitude and fury of the catastrophe that was approaching by leaps and bounds. Valencia collapsed and the Levante players did not return to normality in the regular competition until the birth of November. Matches and training sessions were suspended until the chaotic situation changed.

At that point in the story, the calendar took an extraordinary turn of events. The impossibility of playing the matches at home led to the exodus of the blue and red squad to unknown territories. It was an accidental and fortuitous solution. Urquizu’s men were left with no choice but to gather their belongings, and to pull on their resignation, in order to face the four linked trips that were on the horizon. One would have to imagine the state of the national roads to exacerbate the group’s excursionist tendency. And the buses of the past did not have the comfort of today’s vehicles.

Elda and Alcoy (matchdays eight and nine) seemed to mark a small truce in this colossal adventure. Levante had not taken to the field since matchday five. However, the distances took on a new dimension, coinciding with the league clashes against Cádiz (matchday ten) and Recreativo de Huelva on Sundays 17 and 24 November, although the match against Recre was on matchday six. The balance of results, from a general perspective, was not particularly encouraging. Levante went down to the wire against Eldense (3-1), Cadiz (3-1) and Recre (2-1) and broke that negative trend at El Collao against Alcoyano (1-2). Paredes clinched the victory in the final minutes of the game.

The match against Recreativo de Huelva marked Urzquizu’s farewell to the Granada bench and his replacement by Álvaro. The most travelled version of Levante aggravated their depressive state of mind. The team had been wandering around the darkest part of the table in the days prior to the flood. Defeat in Huelva pushed the club into the relegation places in the Third Division. However, everything changed during an uplifting second half of the season. The match against Extremadura (4-0) on 1 January 1958 (seventh matchday) marked a stubborn frontier, but what happened with the clashes against Eldense, Alcoyano, Cádiz and the shelter of Vallejo? Between March and April 1958, the wins came 6-1 and 2-0 against the representatives from Alicante and 5-0 against the team from La Tacita de Plata to definitively transform the inertia of a team installed in the highest part of the classification.