Home / España Libre Cup / Historical Context

Historical Context

On Sunday, the sixth of June 1937, Levante F.C. played against Gerona at the Vallejo stadium. The chronicles highlight that the rain dampened the evolution of that match (2-2). The date is relevant for sporting reasons. It was the starting point for the development of the Copa España Libre. The date also conceals allegorical aspects. At that time Pablo Picasso was putting the final touches to Guernica, an emblematic work of his time, which was to be exhibited at the International Exhibition in Paris in the summer of 1937. On Sunday 18 July, El Mundo Deportivo emphasised the significance of the competition.“Perhaps as the years go by, in the line for 1937 the word UNPLAYED appears instead of the winner would be unfair. It would be, even if the Cup had this strange and unsportsmanlike formula. It would be all the more so because the players, who are sportsmen and disciplined, have done honour to the Tournament and have played it with all their commitment and interest». That day Levante F.C. and Valencia F.C. challenged their destinies in the Sarriá Stadium: The Final of the Copa España Libre sanctioned Levante’s superiority thanks to the goal scored by Nieto (1-0). Levante were enthroned as champions.

The Copa España Libre formed part of a historical context dominated by pain and terrible uncertainty. The competition evolved between the months of June and July, although its genesis must be sought earlier in time. As in the years that followed, the Cup ended an anomalous sporting year after the outbreak of the Civil War. Since October 1936, in Spain loyal to the Republic, there is evidence of work aimed at structuring a football calendar for the 1936-1937 season following the usual formula, although conditioned by the war. As a rule, Ricardo Cabot always appears as the representative of the Spanish Football Federation. The Super-Regional Championships, the Liga del Mediterráneo and the Copa España Libre are in line with this approach, but what was happening in the old Iberia while the teams of Levante, Valencia, Gerona and Español competed on the pitch for the Trophy donated by the President of the Republic?

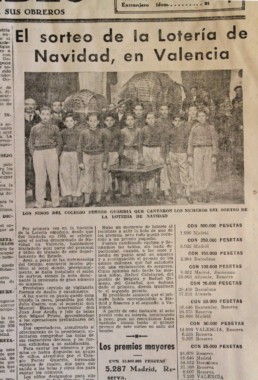

The war broke out on 17 July 1936 with the military insurrection that had Melilla as its epicentre. From the Protectorate, the rebellion spread to the Iberian Peninsula to create a country divided into two antagonistic and totally irreconcilable spaces. Valencia maintained an unwavering loyalty to the structures of the Second Republic established at the ballot box in April 1931. Its commitment was resolute and from the clarity of November 1936 it proudly assumed the functions of capital of the Republican Government. The change of residence of the government meant that for about a year the main decisions were taken from Valencia. The Republican Government’s activity in the capital of the Turia was copious. There were some unique situations. Valencia hosted a congress of world-class intellectuals in the summer of 1937. In December 1936, the traditional Christmas lottery was held in Valencia. For the first time in the history of the Spanish lottery since it was founded in 1763, the draw was held in the city of the Turia. Valencia sheltered refugees from different parts of Republican Spain and housed collections linked to the Prado Museum. Emblematic spaces such as the Torres de Serranos and the Convent of the Patriarch housed collections from the National Artistic Treasure of the Spanish art gallery.

During the spring of 1937, while the Levante teams were preparing their assault on the Copa España Libre with friendly matches, the military chessboard was perfectly defined. The battle for the strategic strip of northern Spain pitted the Republican army against the Nationalist side. The military plans of the rebels had changed in view of the obvious impossibility of occupying Madrid. Repeated failures led to a substantial change in strategy. The war would drag on in space and time. The Nationalists focused on the Republican territories in the north. Biscay, Santander and Asturias attracted attention. These regions hid an attractive booty from an economic perspective and from a symbolic point of view, as they definitively fragmented the Second Republic. There was no truce. The guns were howling with virulence at that time.

The offensive on Biscay began on 31 March 1937. Military operations were concentrated on the front, but the civilian population felt helpless and defenceless. German Condor Legion planes razed Guernica and Durango to the ground in the final days of April 1937. Guernica became the expression of barbarity and terror and the clearest paradigm of the new meaning of the conflict. The Government of the Republic, presided over by Juan Negrín, denounced to the League of Nations the fury of the bombings, which were the most absolute metaphor for barbarism. The repercussions in Old Europe were immediate. The headlines of such representative newspapers as The Times, Daily Herald, The Daily Telegraph, and L’Humanite presented the devastating atrocities committed to the world.

Levante’s first goals in the trophy coincided with a tightening of the siege on Bilbao. On 18 July 1937, Manuel Azaña reflected at the University of Valencia on the transformation that the war had undergone due to the support of various foreign powers (Italy, Germany and Portugal) for the insubordinate soldiers. The President of the Second Republic spoke openly of invasion and criticised the passive attitude of France and England. That Sunday, in Barcelona, Nieto celebrated the goal that validated Levante’s victory in the Copa España Libre. Bilbao had already fallen into the hands of National Spain. The Republican attack on Brunete led to the interruption of operations in the North. It was a temporary halt. The offensive on Cantabria resumed in August. A few months later the conquest of the North was completed after the subjugation of Avilés and Gijón.