Home / España Libre Cup / The Meaning of the Cup

The Meaning of the Cup

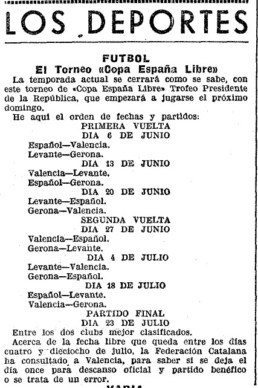

Fortunately, the story that extols and magnifies the colossal participation of Levante F.C. in the universe of the Copa España Libre, Trofeo Presidente de la República, popularly known by Levante fans as Copa de La República, between the months of June and July 1937, acquired the deserved varnish that, in a time not so far from the present, it had lost. It was the typical narrative that plunged into the darkness of darkness to languish and lose the trace of its heartbeat for countless decades. That trail that once shone brightly faded into obscurity. It is common for history not always to invoke the defeated. And the Cup was played on soil devoted to the government of the Republic barely a year after the military uprising, dated July 1936, by the troops led by General Francisco Franco. July 2020 marks the 83rd anniversary of a feat that could be described as titanic, given all the conditions that had to be overcome to combine football with a monstrous war that threatened to change the course of a country that had embraced republicanism after the elections of April 1931.

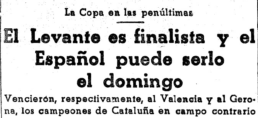

Fortunately, the story is now perfectly syndicated in the history of Levante. From a sporting point of view, Dolz’s action in the second half of the match between Levante and Valencia at the Estadio de Sarrià is particularly noteworthy. Agustinet tempered the ball decisively on the edge of the Valencia area. It was a suggestive invitation that Nieto, with the soul of a corsair, did not miss. The striker emerged from there to change the destiny of a rough game. The chronicles of the time warn: It was not an aesthetic confrontation. It was a bloody fight between two entities accustomed to rivalry on the pitch. More categorical and solemn was the preview presented by El Mundo Deportivo on the day of the match. «This afternoon’s match has a more important significance. It is the FINAL OF THE 1937 CUP. And its significance lies in the fact that in loyal Spain football competitions have not been interrupted. After the super-regionals, there was the League. Now also the Cup Final which, as in previous years of the Trophy’s glorious history, is donated by the Head of State», (alluding to Manuel Azaña).

The memory of the Copa España Libre now seems to have been restored. The memory and the thread of that competition seems to have been restored, although it still lacks officialdom, but it was not always like that. There was not always news of a title that the fearsome and cruel oblivion had postponed and scorned. That trophy had been relegated to neglect. It remained cornered in the suburbs of memory to fade away. Countless sediments had buried it until it disappeared from the map of memories. The darkness engulfed it. It was defenceless and helpless, even though the Cup remained among the trophies that guarded the hall of prizes won by the Club during its history with an unmistakable legend that despite the passage of time maintained its effervescence.

«Copa España Libre, Trofeo Presidente de la República». Pride of belonging. It was only necessary to read carefully and value history in order to rehabilitate its splendour. The Cup lay dormant as a witness and evocation of what once happened in a country scorched by flames. Confused, it was chained to oblivion. It must have been so because the Copa España Libre was in the exhibition that the organisation organised at the Ateneo Mercantil on the occasion of the inauguration of the current Ciutat de València Stadium in September 1969. Years later, it formed part of the collection linked to the exhibition that commemorated the 75th anniversary of the institution’s existence at the Bancaja hall. It was even in the marquee that the club erected on Avenida de Aragón during the 1995-1996 Promotion to Second Division A competition.

There was a moment when everything was yet to be discovered. Perhaps the conventual silence mortified her soul. She, who had received the praise of the Valencian fans on a metallic Sunday afternoon on 8 August 1937 in Vallejo, survived between stealth and shame. No one dared to rescue her. Nobody knew the significance of that feat. Nobody knew about the title that a team of brave men had one day won. All were unknowns to be solved. Nobody knew anything about its name. Nor about the meaning behind that heroic triumph. Nobody seemed to want to vindicate their honour. There is no greater fate than not knowing the meaning of your own history. That Cup contained pride, it exhumed honour, although it was the metaphor of a sadly announced failure. It was the symbol of a period characterised by barbarism. The most absolute manifestation of how memory can be adulterated to fall into oblivion.

Perhaps the fascination that the rediscovery of this story has generated in the imagination of the Levante fans can be traced back to the clandestinity that the Copa España Libre exudes. It may seem a contradiction in terms, but deep down it is not. It is not a simple paradox. It is the myth of the underground and the heroic myth of resistance. Stories of losers have always been enchanting. And this looks like an underdog story to the nth degree. In other disciplines there are countless examples of fascinating losers. It is a recurring theme in literature and film. It also happens in football. The trace of that competition faded with the stroke of a pen after the end of the Civil War. 83 years later, the rehabilitation process is still not complete.

The story of the Copa de La España Libre is captivating because of the complexity of its achievement, in the context of a terrifying war, and because of all the obstacles and obstacles that have occurred since its resurrection at the dawn of the third millennium. In fact, its recognition is still unfinished. Therein lies its main uniqueness. And its seduction. The Cup seems like a metaphor for Levante’s worn-out history. Perhaps it has endured and has become anchored in the consciousness of the azulgranas fans due to the complex difficulty involved in the definitive recovery of its memory. The Levante fans, from the aggravation and outrage, feel that the Copa España Libre belongs to them. It was a title won against the tide that time seemed to eclipse. It is perhaps the best legacy of a trophy that has allowed the notion of club to grow. Perhaps it is time for the hero it conceals to be reborn.